Travel-Related Diarrhea, Evidence-Based

When we travel, we introduce our bodies to new microorganisms via what we ingest for food and drink. This has the potential to disrupt our internal gut microbiota balance and cause diarrhea, or frequent loose watery stools.

Literature Sources

1) "Double blind trial of loperamide for treating acute watery diarrhoea in expatriates in Bangladesh." (1989) by F P van Loon and others. Link to Article.

2) "Prevention of travelers' diarrhea by nonantibiotic drugs" (1986) by R Steffen and others. Link to Article.

3) "Antimicrobial activity of bismuth subsalicylate on Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli O157:H7, norovirus, and other common enteric pathogens" (2015) by Adam M Pitz and others. Link to Article.

4) "Increased Risk for ESBL-Producing Bacteria from Co-administration of Loperamide and Antimicrobial Drugs for Travelers' Diarrhea" (2016) by Anu Kantele and others. Link to Article.

Traveling is a popular activity for many people. It is a way to explore new environments, languages, cultures, and foods. However, something that is often overlooked is a new microbiota. Microbiota refers to the composition of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protista in a local environment. When we travel, we introduce our bodies to new microorganisms via what we ingest for food and drink. This has the potential to disrupt our internal gut microbiota balance and cause diarrhea, or frequent loose watery stools.

Not all foods and drinks have the same risk for causing this imbalance. Essentially, the more sterile the food or drink, the less risk it poses to changing your gut microbiota. Depending on where you go, hygiene practices may not be prioritized to reduce the spread of microorganisms. Therefore, the best ways to prevent travel-related diarrhea are to avoid places with questionable kitchen cleanliness and to clean foods and drinks yourself before consuming them.

Fortunately, even if you get travel-related diarrhea, it is typically self-limiting. The body naturally tries to flush out the offending agent by increasing gut motility and gut water secretion. It wants to restore your microbiota balance that was offset by what you ate. Most cases of this type of diarrhea resolve themselves within a week but dehydration is a major health risk. Not only do you lose water with diarrhea, but you also lose electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate. Oral rehydration solutions are ideal for replenishing these lost electrolytes along with water.

For those who are unable to wait until the diarrhea clears itself naturally, there are medications available that can aid in its resolution. In study #1, researchers compared loperamide to placebo for patients with acute onset diarrhea. Loperamide is an opioid-like chemical that decreases gut motility and allows for more water to get absorbed from the gut. The chemical is minimally absorbed into the bloodstream and doesn't affect the brain so it is unlike most opioid-like medications. In this study, patients took either loperamide or a placebo after each unformed bowel movement for 5 days. In the loperamide group, on day 1 of the study, there was an average of 2.5 bowel movements per day, compared to about 4 per day for the placebo group. This improved to 1.5 bowel movements on day 2, compared to 3.5 for the placebo group. At the end of the study, bowel movements were comparable between the two groups at about 1 per day.

Essentially, the loperamide hastened a reduction of bowel movements. This is a good thing for non-infectious diarrhea, but caution should be regarded when using this chemical for infectious diarrhea, especially in children, as the chemical disrupts the body's ability to quickly clear the infectious agent and can prolong exposure to the pathogen. Due to that concern, researchers, in this study, excluded patients who had high fevers (greater than 39 degrees Celsius), blood in their stool, or proof of diarrhea caused by Shigella species.

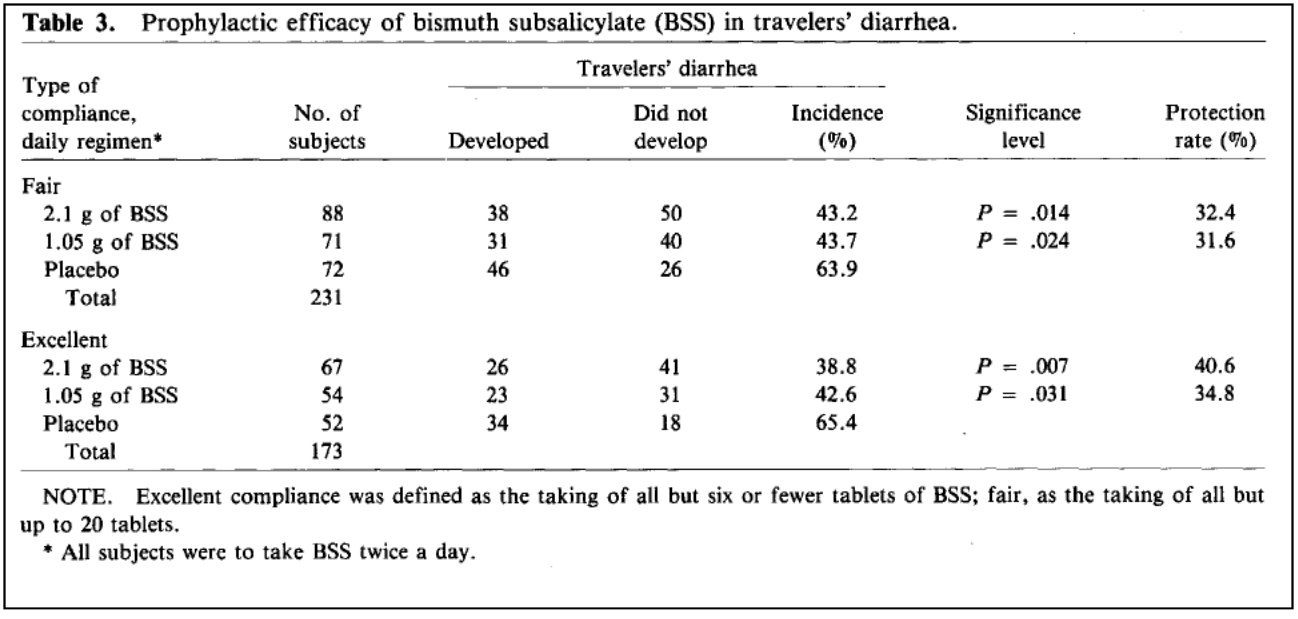

Another study (#2) compared a different chemical, bismuth subsalicylate, against a placebo. Bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) is a molecule containing a heavy metal bismuth that has purported antimicrobial actions and subsalicylate which has antisecretory effects in the intestines. In the study, researchers divided patients into three groups. The first group took two tablets of BSS 525mg twice daily, the second group took two tablets of BSS 262.5mg twice daily, and the control group took a placebo. The goal of the study was to evaluate the effects of BSS to prevent travel-related diarrhea. Patients were in the study for the duration of their travel, between 12 to 28 days.

Those who had excellent compliance with BSS at the higher dose had about a 40% reduction in the incidence of travel-related diarrhea compared to the placebo group.

Study #3 took a further look into the antimicrobial effects of BSS. Researchers examined the effects the chemical has on common intestinal pathogens: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Clostridium difficile, Shigella, and Salmonella in a laboratory environment. The researchers discovered that when exposed to 35mg/mL concentration of BSS, the quantities of all the pathogens were greatly reduced 24 hours after exposure as shown in the table below.

Since this was an in-vitro environment, the results cannot be directly applied to how the medication will work in the human gut environment. Nevertheless, the results provide some insight into how BSS helps with diarrhea.

The most common side effects when using BSS are the presentation of a black tongue and the production of black stool. Bismuth itself when taken orally is minimally absorbed from the intestines thus systemic effects are limited. Nevertheless, when taken in high doses for an extended period, it can present serious systemic risks such as encephalopathy and nephropathy. The subsalicylate portion is readily absorbed and has effects similar to aspirin, another chemical used for pain and inflammation.

What Is The Role of Antibiotics?

Travel-related diarrhea is typically caused by infectious bacteria, but can also be caused by viruses and parasites that are not susceptible to antibiotics. In some cases, the cause can not be determined. The usage of antibiotics for diarrhea can introduce some risk for an unknown pathogen. For example, using them on Shiga toxin-producing E. coli can worsen the diarrhea and cause systemic complications. Some bacteria are resistant to certain antibiotics and taking them can create an imbalance in the gut that allows for the proliferation of resistant bacteria, such as antibiotic-resistant clostridium difficile infections.

Researchers in study #4 analyzed the effects of antibiotics on the rates of gut colonization by antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. They observed colonization rates of about 20% for those who didn't use anything for travel-related diarrhea, 40% for those who took antibiotics, and 71% for those who took them with loperamide, a chemical used to slow down the peristalsis.

Ideally, a stool sample should be obtained to determine what bacterium is overgrowing and what antibiotics it is sensitive to. Then use an antibiotic that has limited absorption into the bloodstream.

Travel-related diarrhea is an uncomfortable reality that many travelers face which can have dire consequences if it is not properly managed. Fortunately, some steps can be taken to make it more of an annoyance than a serious health risk.

Subscribe and Join The Discussion

Subscribe to the email newsletter and stay up to date on the latest posts from Primary Pharmacist. We want to hear your thoughts! Subscribers can also participate in discussions occurring site-wide.